In Search of the Most Massive Star

Astronomers are scouring the universe and their computer models to discover how big stars can be.

In 2006, I found myself gazing through a telescope at the Sun as a small dot slowly slid in front of our star. It was Mercury, an entire world. During the transit, the massive Sun dominated most of the telescope’s field of view. Yet Mercury, which lay much closer to Earth, looked utterly small. It was dwarfed by the sheer size of the Sun.

Compared with the terrestrial planets, the Sun is indeed huge: It’s as massive as 300,000 Earths. Yet our Sun is tiny next to other stars within our galaxy. For example, Antares is 12 solar masses (where one solar mass is the mass of our Sun), and Rigel is around 21 solar masses.

Such comparisons beg the question: How big can stars get? Can they grow arbitrarily large, or is there some fundamental process that halts a star’s growth at a certain mass when it first forms?

There are two different ways to answer this question. The first is with observations. Truly massive stars are rare. However, if we look at enough stars, we can obtain a sufficient statistical sample to see if there is a limit to how massive stars can be.

The Perfect Sample: Arches

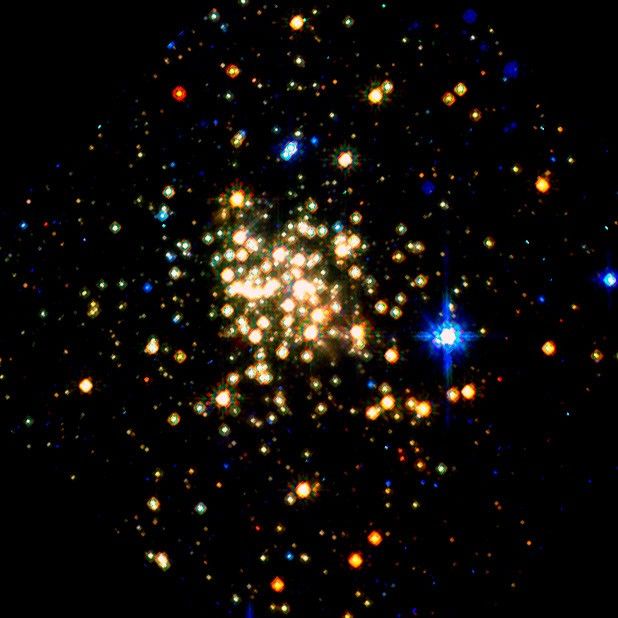

In 2005, astronomer Donald Figer (now at Rochester Institute of Technology) found a perfect place to obtain this statistical sample: the Arches cluster. Arches is a beautiful open cluster in the constellation Sagittarius. As the densest cluster in the Milky Way, it contains 11,000 solar masses’ worth of stars. If the area around our Sun were as populated as Arches is, there would be more than 100,000 stars between us and our nearest star, Proxima Centauri.

Arches, the densest cluster in the Milky Way. Credit NASA, ESA and D. Figer (STScI)

Another reason why Arches is a perfect place to search for massive stars is that it is young. Massive stars live fast and die young, burning through their nuclear fuel within a few million years. As far as clusters go, Arches is a baby at 2½ million years old. To put this in perspective, our hominid ancestors were walking on Earth before Arches formed. Figer calculated that Arches was young enough that if stars up to 500 times the mass of our Sun had formed there, they would still be shining today.

Observing Arches is not easy, however. It’s 25,000 light years from Earth, and its stars are packed so tightly that they are difficult to resolve individually.

Yet, even with these difficulties, Figer found stars with up to 130 times the mass of our Sun. But he didn’t find any stars even close to 500 solar masses. Figer concluded that stars of 150 solar masses or more simply couldn’t form.

The results were convincing. After that, astronomers used 150 solar masses as the limit for how large a star could be. But the Tarantula told a different story.

Massive Nebula, Massive Stars

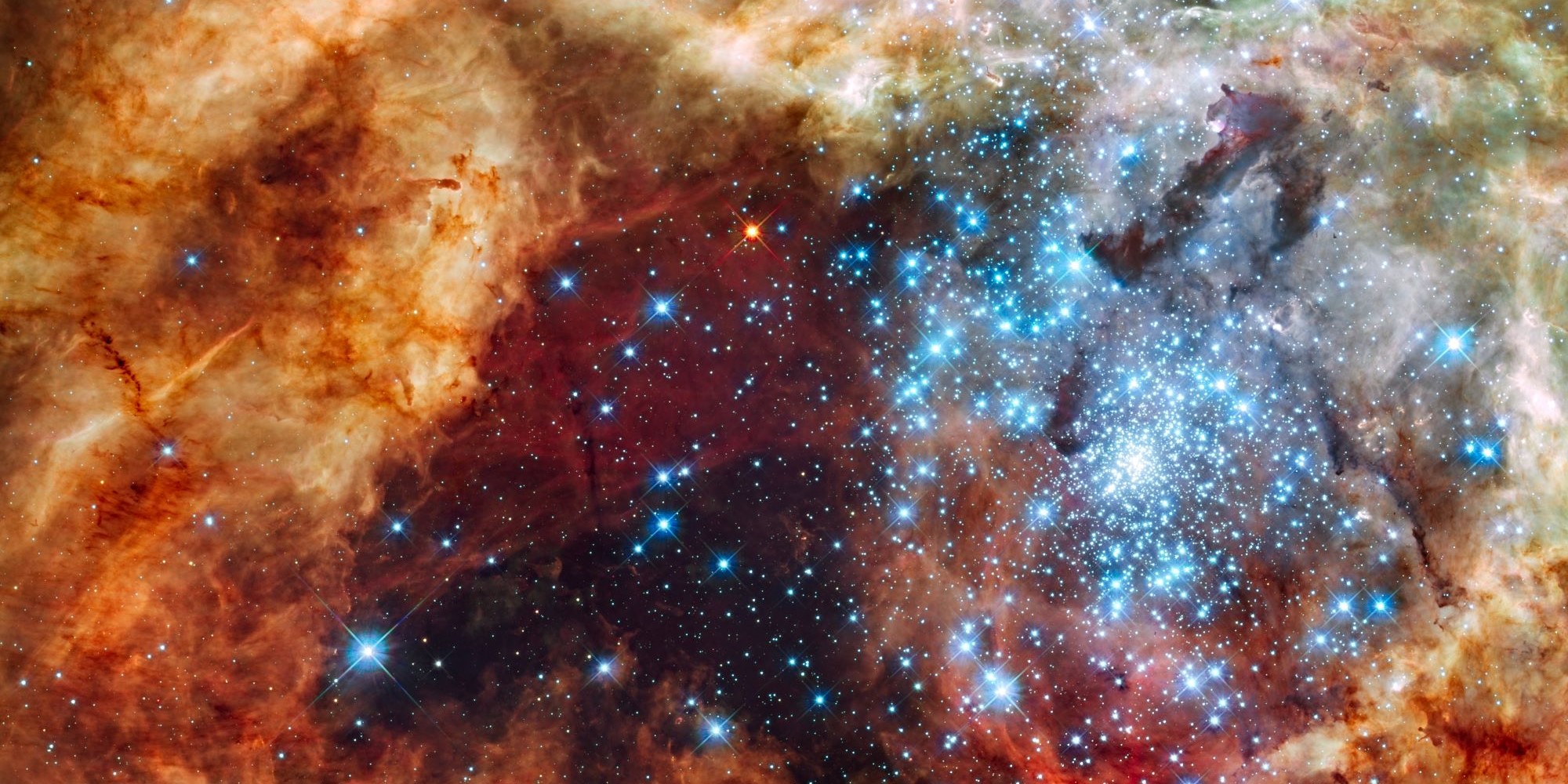

The Tarantula Nebula, located in the Large Magellanic Cloud some 160,000 light-years from us, is one of the most massive nebulae known. Light takes more than 500 years to traverse its extremes. It is so huge that if it were located where the Orion Nebula is (some 1,500 light-years from Earth), it would have an angular size of about 20°, about the diagonal size of the Great Square of Pegasus.

Such a giant nebula creates an opportunity for more massive stars to form, explains Paul Crowther (University of Sheffield, UK). Only a small percentage of gas in a nebula will end up in stars, so the more massive a nebula is, the more raw materials it has to work with. If there are stars larger than 150 times the mass of our Sun out there, then the Tarantula Nebula is an ideal place to look for them.

When the Gemini South telescope in Chile set its sights on the middle of the Tarantula Nebula in 2021, it was able to resolve stars in the massive cluster at its center, R136. A star within this cluster, R136a1, is the most massive star yet dis covered. Various studies peg it at anywhere from 200 to more than 300 times the mass of our Sun.

R136a1 is not alone. There are hundreds of massive stars lurking near the center of this nebula, ranging from a few tens to hundreds of solar masses.

These stars may have even started out more massive than we see them today, says Erin Higgins (Armagh Observatory and Planetarium, Northern Ireland). That’s because very massive stars often have strong winds, which propel gas out and away, whittling the star down over time. These winds can be so strong that the star can lose a fifth of its mass within a million years.

Observations from the Tarantula Nebula indicate that perhaps the limit to stellar mass is around 300 Suns — that is, if the stars there didn’t begin life larger. But again, is this the whole story? Is there any way to build an even bigger star? To answer this question, astronomers turn to a second approach besides observations: the theory of how stars form.

A Galactic Cookbook: Stellar Edition

In order to build a massive star, you need a lot of gas. Pressure from the motions of warm gas counteracts the cloud’s own gravity and keeps it from collapsing. In this way, a nebula can remain stable . . . for a while.

Compression can come along and upset this balance. A nearby supernova could compress the gas, or a shock wave from a collision with another nebula or galaxy could ripple through a cloud to initiate collapse. Density waves within a galaxy can also squeeze the gas — we see the results of these waves in the starbursting spiral arms of many galaxies (S&T:Mar. 2023, p. 14). But compression from the outside isn’t always necessary: Perhaps the gas is simply clumped just enough that its own gravity wins.

Whatever the cause, when the gas is squeezed, gravitational collapse can begin. The gas will fragment into smaller and smaller chunks. Eventually, these chunks develop into cluster of protostars, which continue to grow as gas pours in. Researchers starting in the 1970s pointed out that, once a growing star reaches 20 solar masses, the outward pressure from the star’s own photons should clear away the remaining infalling material. But if this were the whole story, then stars would not be able to grow beyond 20 solar masses.

Subsequent work has shown that the remedy lies in the star’s accretion disk. This disk encircles the forming star and channels material down onto it; feeding from the disk is how a protostar grows. The disk also funnels the star’s outpouring radiation in certain directions, limiting its ability to erode the infalling gas.

The disk helps determine how big the star will be. While neat accretion disks typically lead to modest-size stars, larger stars form more chaotically, with streams of infalling material acting like conveyor belts, dumping gas onto the forming star in sudden bursts.

Although theoretical models aren’t perfect, they do allow us to tweak variables to see how environment affects stellar mass. Models also allow us to envision the conditions in a location that is very difficult to observe — the early universe — to see if the first stars could have been more massive than their modern-day counterparts.

Artist’s conception of an accretion disk around a forming star. Credit NASA-JPL, Caltech

Long Ago and Far Away

Donghui Jeong (Penn State University) and James Gurian (Perimeter Institute, Canada) use computer modeling to understand the characteristics of the first stars, which formed more than 13 billion years ago. Their models are missing one thing that stellar models of the nearby universe include: a rich array of elements.

All elements heavier than hydrogen, helium, and lithium were formed thanks to stars — either in stellar fusion, in stars’ deaths, the collisions of stellar remnants, or by the later breakup of the atoms that stars make. With no stars before them to make heavy elements, such as carbon and iron, the first generation of stars should have been pristine. These stars are dubbed Population III stars.

Heavy elements can have a major impact on a star’s birth and evolution. Jeong explains that two of the most important ingredients in determining the final mass of a Population III star are rotation — which can determine how much gas falls onto the protostar — and how efficiently that infalling gas can cool. Heavy elements affect the latter.

It may seem counterintuitive, but gas must first cool before it forms a star: Gas that is too hot will resist gravity’s inward tug. As gas radiates away this energy, it can collapse and become gravitationally bound. This cooling occurs due to collisions within the gas cloud. Collisions can excite electrons within an atom or a molecule, or the collision’s energy can be stored in the atom or molecule’s rotational or vibrational modes. When the atom or molecule releases this energy again, it may emit a photon, which carries away some of the energy within the gas. Thus, the gas cools.

Heavy elements can host electrons at a wider variety of energy levels than hydrogen or helium can and have more available rotational and vibrational modes. If there are heavy elements present in the gas, then there are more ways for atoms and molecules to lose energy, and the gas can cool more efficiently. Conversely, without heavier elements, the gas has a more difficult time cooling. In this case, gas would not be able to fragment into smaller clumps as efficiently. Instead of forming a rich stellar cluster, a gas cloud might

only make a few giant stars.

In the team’s models, Population III stars end up with a couple hundred solar masses. Other groups have produced much bigger stars, though, some of them reaching a gargantuan 1,000 solar masses.

Astronomers can combine such theoretical models with observations of stars forming very early in the universe. While Population III stars remain beyond our reach for now, other stars may help us learn how star formation kicked off and how massive these early stars were.

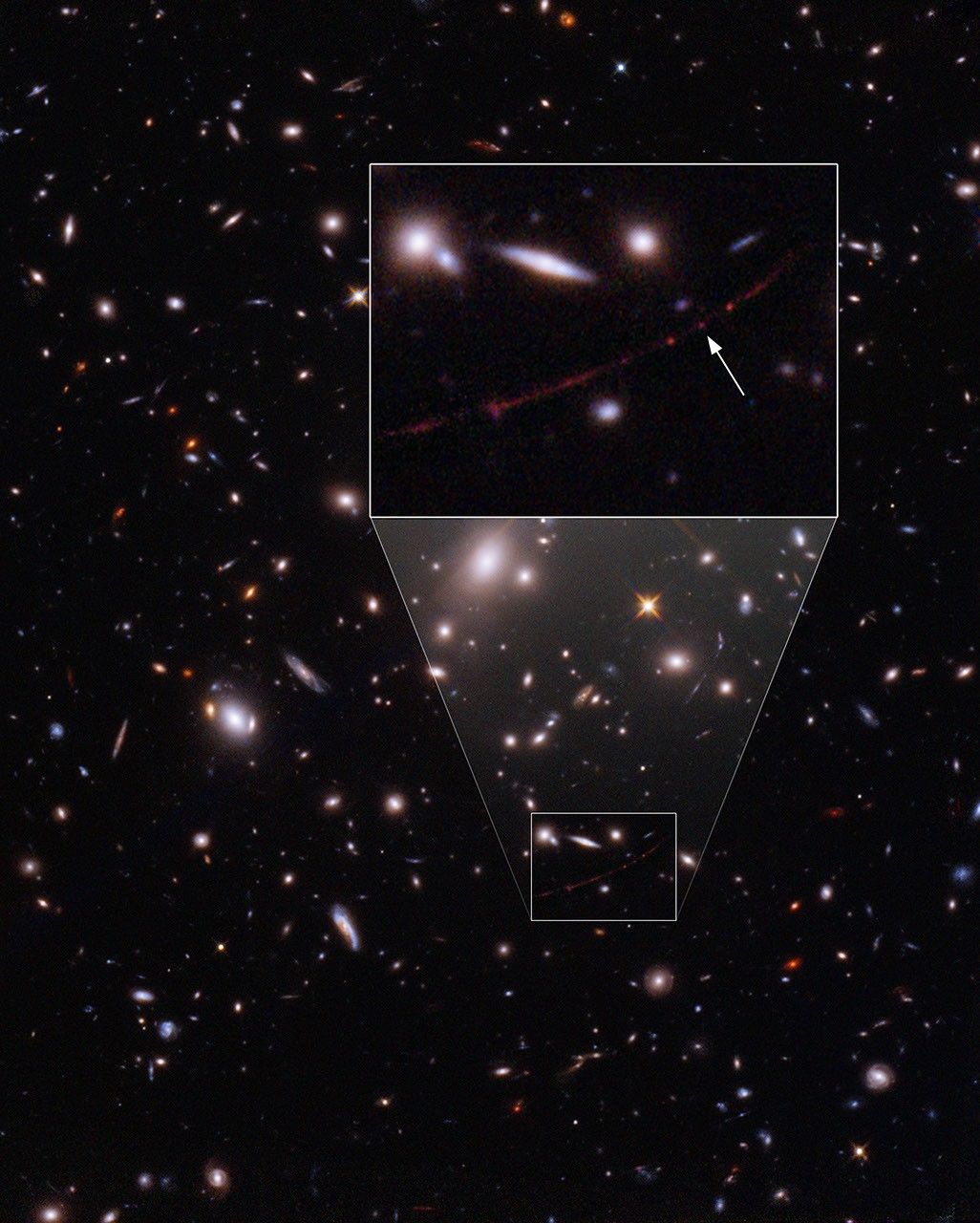

One of the most distant stars observed so far is Earendel, shining at us from only 1 billion years after the Big Bang (S&T: Aug. 2022, p. 11). This star lies behind the massive galaxy cluster WHL0137−08. The cluster’s gravity acts like a giant magnifying glass, amplifying the light of objects beyond it, including Earendel, enough that we can see them. If Earendel is a single star, then it may be anywhere from 20 to 200 solar masses.

The most distant star, Earendel, magnified by a gravitational lens. Credit NASA, ESA, Brian Welch (JHU), Dan Coe (STScI); Image Processing: NASA, ESA, Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

It is also possible to investigate how massive early stars were using more indirect methods. For example, astronomers can search for specific elements and isotopes and their relative abundances in early galaxies. These chemical patterns can tell us about the mass of stars that produced them. The chemical makeup of one of the most distant galaxies ever imaged, GN-z11, may indicate gargantuan stars have formed there. This galaxy, located only about 440 million years after the Big Bang (at a redshift of about 11), has high

levels of nitrogen and low levels of oxygen — in fact, the ratio of nitrogen to oxygen is four times what is seen in our Sun. A group of astronomers led by Corinne Charbonnel (University of Geneva, Switzerland) recently suggested that this over abundance of nitrogen implies that GN-z11 hosts truly massive stars — on the order of 5,000 to 10,000 solar masses! However, Chiaki Kobayashi (University of Hertfordshire, UK) and Andrea Ferrara (Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa, Italy) suggest that such an abundance pattern could instead be created by starting, stopping, and then re-starting star formation. In this scenario, hot, blue Wolf-Rayet stars on the order of about 100 solar masses add abundant nitrogen after the second burst of star formation. Another group led by Roberto Maiolino (University of Cambridge, UK) suggests that this abundance pattern could be created by an accreting black hole of about 1 million solar masses.

One specific chemical abundance pattern is made by what are called pair-instability supernovae. Theoretically, for a Population III star between about 140 and 260 solar masses, conditions in the star may be just right so that the gamma rays created by nuclear fusion start converting into electron positron pairs. Unlike photons, these particles do not exert the pressure necessary to hold the star up against the force of gravity. The core collapses.

The collapse triggers more fusion, creating more gamma rays, which in turn create more electron-positron pairs. The core suddenly ignites in a runaway reaction, causing an explosion that completely demolishes the star: No neutron star or black hole is left behind, and all of the elements produced during the star’s life and death are thrown into space, enriching the surroundings.

A pair-instability supernova should leave behind a very particular chemical abundance pattern, one that many astronomers are searching for. If detected, it would mean that Population III stars can reach at least 130 solar masses. Astronomers have found a star with hints of this pattern, but it has yet to be confirmed.

True Stellar Monsters

There’s one final reason to suspect that early stars could have been large — very large. If some stars were incredibly massive, then that could help explain one of the biggest mysteries in astrophysics: how the first big black holes formed.

In almost every large galaxy lurks a supermassive black hole, weighing on the order of millions to billions of times the mass of our Sun. Observations show that massive black holes were in place within galaxies when the universe was only a few hundred million

years old (S&T: May 2024, p. 20). If these massive objects started their lives when a Population III star collapsed into a black hole, packing all of its roughly 100 solar masses inside, then it’s difficult to explain how the black holes grew by a factor of 1,000 or more

so quickly.

Some astronomers thus claim that supermassive stars might have been the seeds of these monstrous black holes instead. These gigantic stars, with tens to hundreds of thousands of solar masses, would have collapsed directly into black holes. To form one of these massive stars, a huge amount of gas would need to collapse, without fragmenting into smaller chunks. This requires a careful balance of conditions that is difficult to achieve but might be possible in the early universe.

“In principle, there is gas, and if you’re able to find a way to condense all of this [gas] . . . into a bound object, then you’re done,” says

Ferrara, who studies star formation in the distant universe. “They would live a very short time, and then they would collapse into a black hole.”

It’s unclear how truly starlike these objects would be. Hydrogen fusion might briefly ignite inside a supermassive star. But it’s also possible that the supermassive star might skip the fusion phase altogether. In that case, the core would be so dense that it would collapse into a black hole without throwing off the immense weight of the surrounding layers. What’s left is a “star” with a black hole at its center, which eats the object from the inside out. Material falling into the black hole would heat up as it falls inward, and this heat would make the quasi-star glow. These objects aren’t stars in the traditional sense but are a new type of object altogether. Perhaps, then, we can define the maximum size of a star as the greatest mass at which a supermassive star will sustain fusion instead of collapsing directly. Unfortunately, we don’t know exactly what that mass is. Both the calculations and the observations are complex, and the maximum mass varies depending on the effects of general relativity on a supermassive star’s stability and how quickly gas accretes onto the star. This process could lead to stars on the order of tens of thousands of solar masses.

But that, of course, assumes supermassive stars ever existed, and that we have gotten all of the physics right.

The Search Continues

So how massive can a star be? We’ve come a long way in the past two decades, but we still don’t have an exact answer. Star formation is a complex process, and there are many factors that can influence how large a star is when it’s born. In our local universe, it seems that stars can reach hundreds of solar masses, while in the early universe, they may have been thousands or even tens of thousands of solar masses.

More definitive answers will not come easily. Some astronomers, like Higgins, are working to find a way to estimate stars’ birth masses based on how the stars look now. Others are introducing more complexity into simulations of the messy physics of star formation. And explorations of the early universe — both in observation and theory — continue. For now, the safest answer is the simplest one: We don’t know.